One of the most famous experiments in modern psychology was the Rosenhan experiment. It was part study, part Punk’d prank and a dash of an Ocean’s Eleven heist. Not only was it an exciting feat of planning, it also exposed some legitimate blind spots that mental hospitals still have trouble getting over to this day.

The Plan.

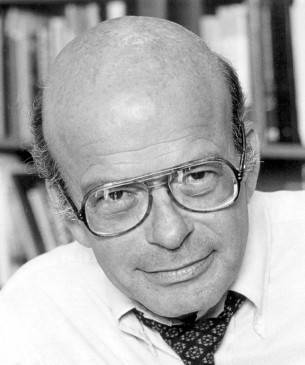

Stanford University professor David Rosenhan and seven of his colleagues gained entry to 12 different mental hospitals, feigning that they could hear voices in their heads. None of the participants had a history of mental illness. The hospitals were never told of the experiment.

The Story.

Each pseudo-patient expressed that they could hear a voice that was the same sex as the patient. The patients claimed the voice in their heads said things like, “empty”, and “hollow”. These words were specifically chosen by Rosenhan as they suggest some sort of existential crisis but are vague enough not to point to any other psychological symptoms. Once admitted to the hospital, the pseudo-patients were to act completely normal.

Treatment by the Hospitals.

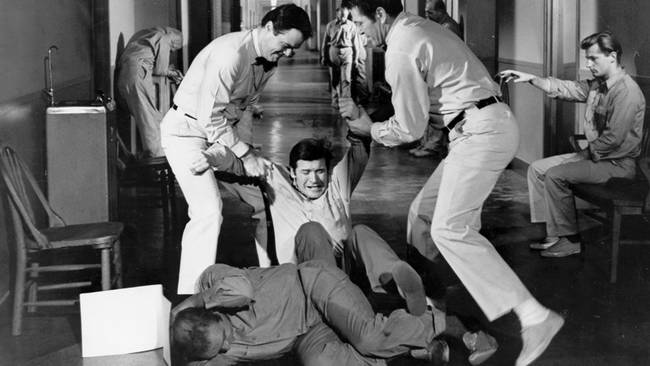

Despite acting like sane people, they all experienced severe dehumanization. The health workers would discuss the patients broadly while in the same room as them. They were needlessly observed while on the toilet. Some even underwent cases of physical and verbal abuse.

The Non-Existent Impostor Experiment.

After the success of the first experiment, Rosenhan was challenged to conduct another experiment at a well-known hospital, who claimed would be able to spot any of Rosenhan’s impostors. Rosenhan agreed. Out of 193 patients admitted to the hospital, 41 were marked by the hospital as pseudo-patients. Funny thing is, Rosenhan had not sent any impostors at all.

Discharged.

Seven pseudo-patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia and one with manic-depressive psychosis. Some only stayed the week before getting released, one stayed 52 days. All were discharged with schizophrenia “in remission”, which Rosenhan points out does nothing for the patient but stigmatizes their mental state. None of the pseudo-patients were identified as impostors, although many patients could tell and even verbally suggested they were running tests.

Rosenhan published the findings of both experiments in Science magazine under the title On Being Sane In Insane Places. It is considered one of the most important studies in mental diagnosis. It proves that, at the time, there was a lot of guesswork in the diagnosis and treatments of patients…and something had to change.

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share