Medieval manuscripts take a lot of forms, and many of them, as well as the information they contain, have helped shape Western civilization as we know it (for better or worse). Many of the surviving manuscripts we have today are religious texts, but there are also scientific works, histories and works of fiction. Besides what the words tell us, the books also teach us about the evolution of language, education and scientific theory. They’re pieces of history that can be traced to today’s culture, and that’s one of the reasons why they’re amazing. When new images of their pages come out, it’s exciting.

Then there’s the Voynich Manuscript.

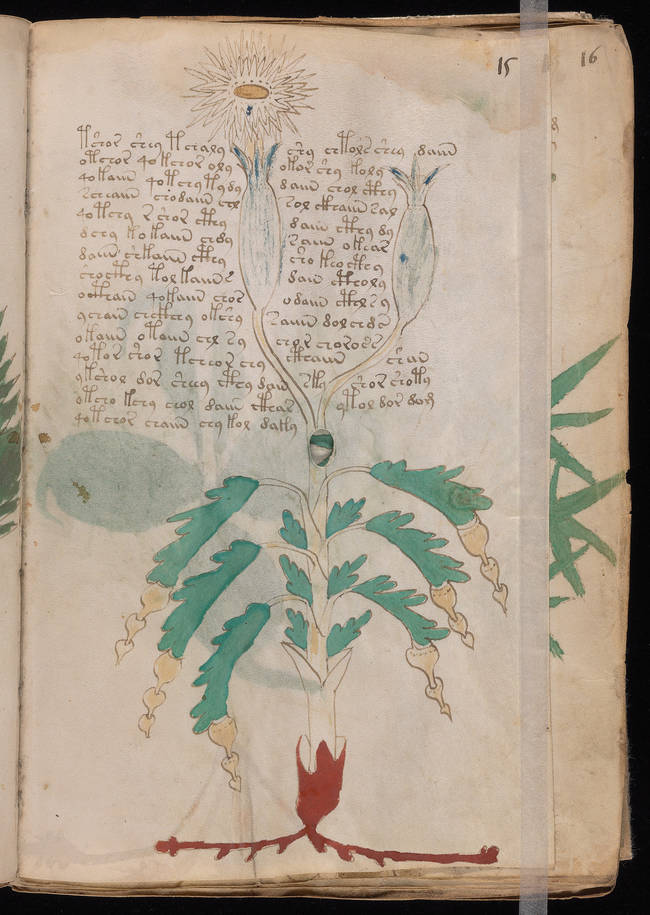

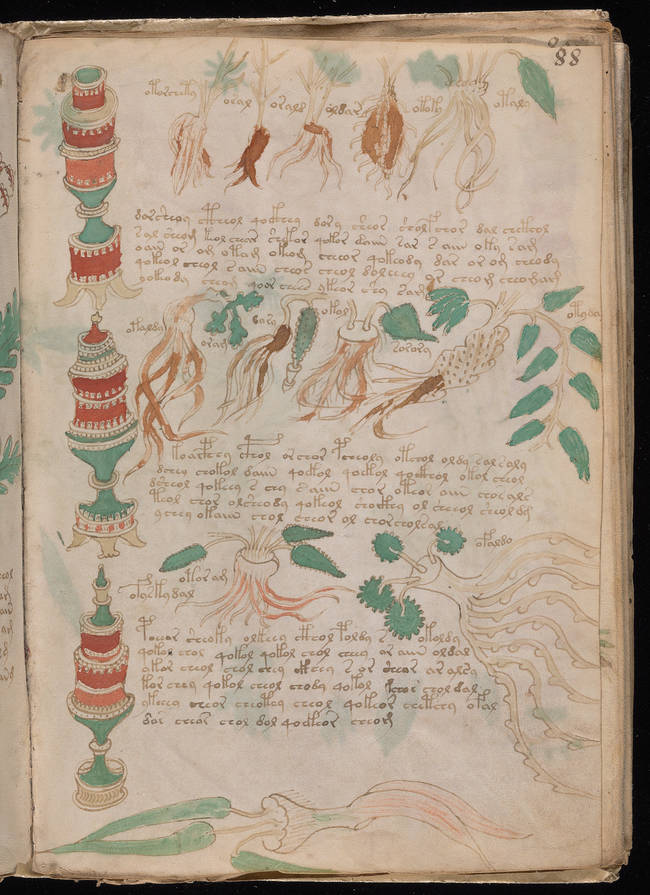

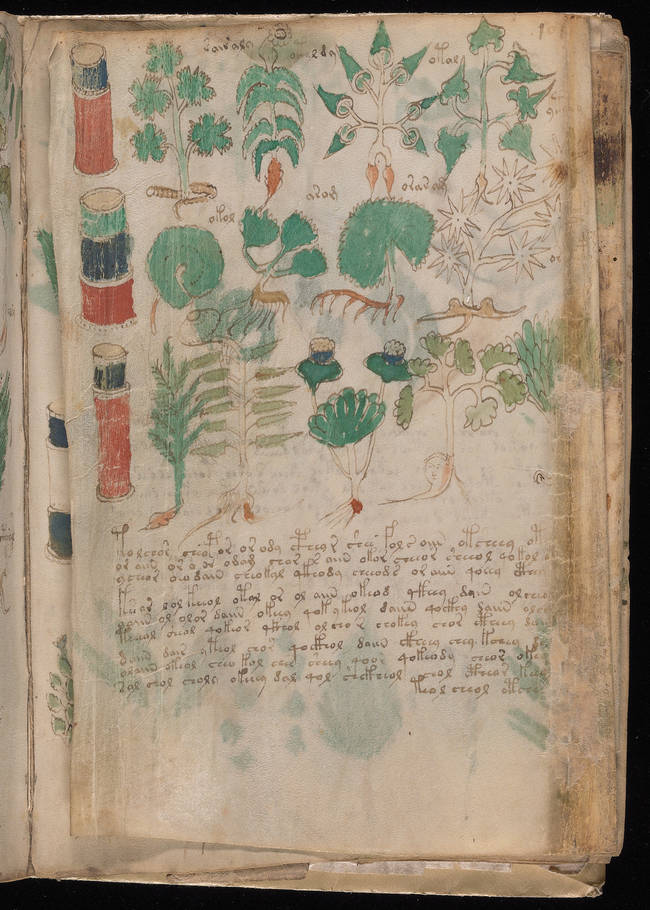

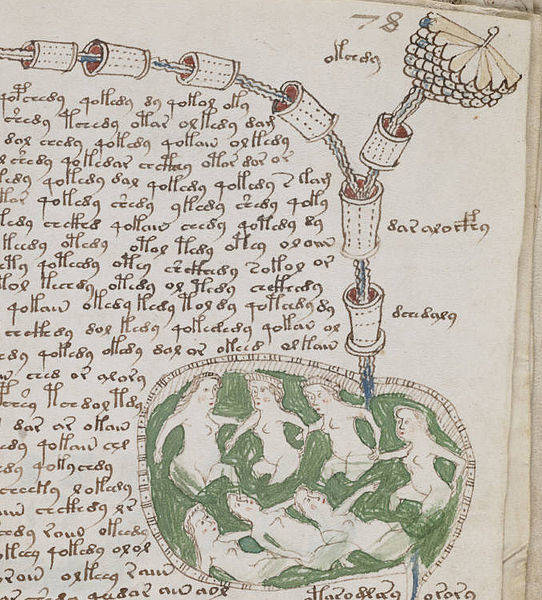

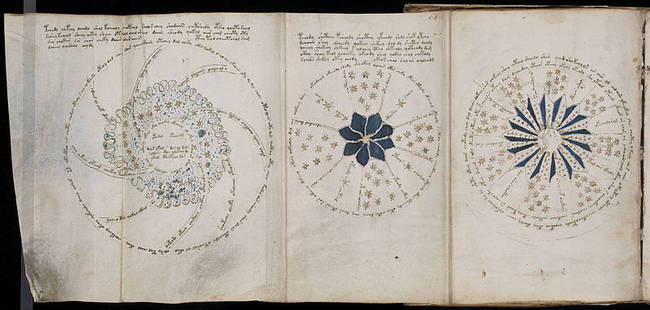

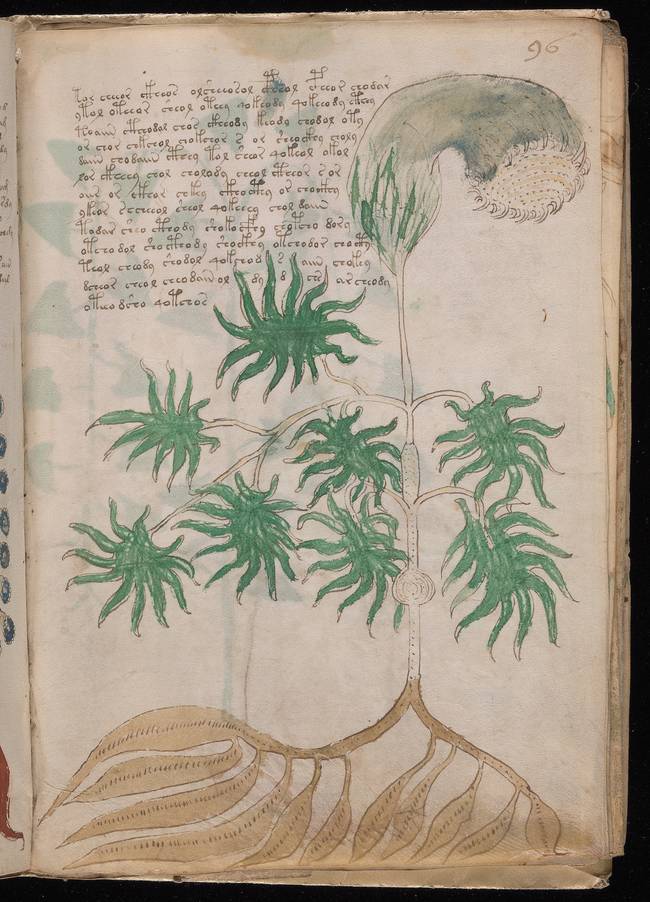

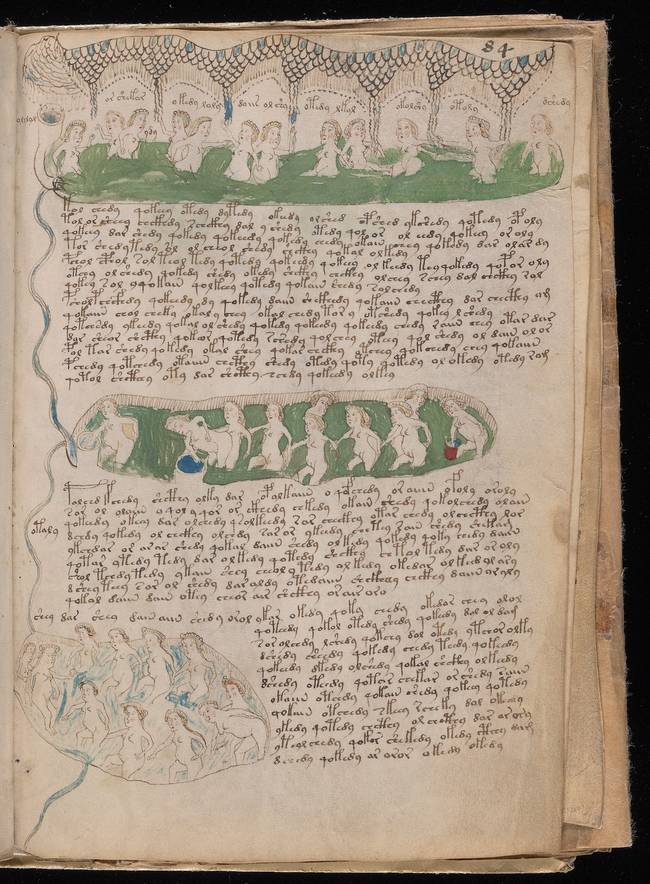

This manuscript was created in Central Europe, possibly Northern Italy, at the end of the 1400s or during the early 1500s. It’s made of vellum and runs some 240 pages, with many dense passages of text. It was named for Wilfrid Voynich, a book dealer who bought it in 1912. It’s actual authorship is unknown. It also includes a diverse collection of images, including 113 species of plants, images of medicines in jars, images of the Zodiac, and a lot of images of people (especially miniature nude women) often shown bathing in tubs. If that sounds weird, don’t worry. It gets weirder.

For one thing, no one can read the Voynich Manuscript. The curly script has been analyzed by linguists, historians, cryptographers and even codebreakers who served in both World Wars, and to this day, no one knows how to begin deciphering the text. For another, those 113 plants depicted in a fair amount of detail? No one has ever agreed on what kinds of plants they are, or if they’re not completely made up. Basically everything in the book, which seems to run from cosmological phenomena to herbalism, seems only almost familiar. Historians think it might have been a pharmacopoeia, or a medicine-making recipe book (astronomy and astrology played a large part in medieval medicine), but with all its oddities, it’s hard to say. Others think it’s a complete hoax, although a carbon dating test of the vellum places it in the right time.

All that confusion doesn’t mean we’re not still trying to figure this thing out, though. Recently, the Beineke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University was able to access some pages that, due to the manuscript’s condition, were not accessible before, and have made scans of the whole thing available for people to look at. So what could this be? A hitherto unknown language showing a practical guide to medicine? The ramblings of a mad monk? Something written in code? A centuries-old conceptual art project? Aliens? (No, no one really thinks it’s aliens.) Maybe we’ll never know.

For now, though, the debate continues. Some think it might have origins in Mexico, based on the plants. A linguist in the U.K. claims to have decoded 14 of the symbols, but that’s all still up in the air. Even if we never figure out what this is, it’s got some fantastic images.

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share