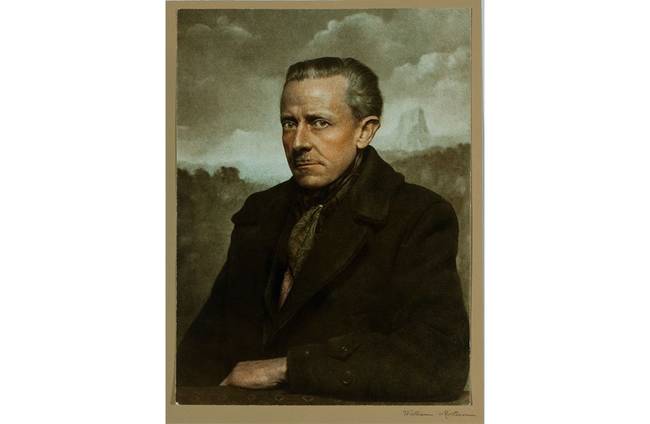

At first glance, William Mortensen’s photographs might not even read as photographs. Many of them were retouched so that the results look more like drawings or paintings than photos. Of course, you might be more interested in the subject matter.

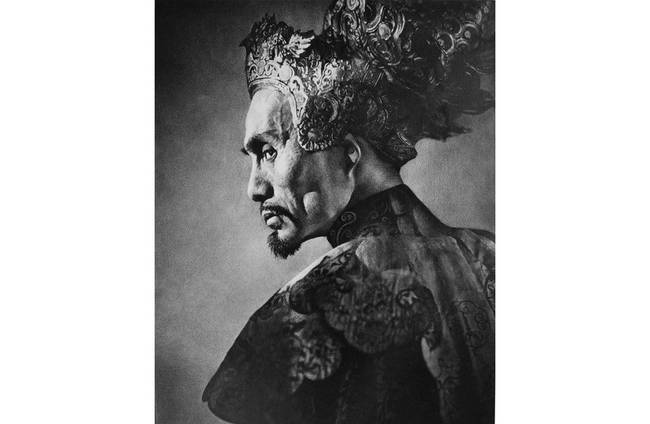

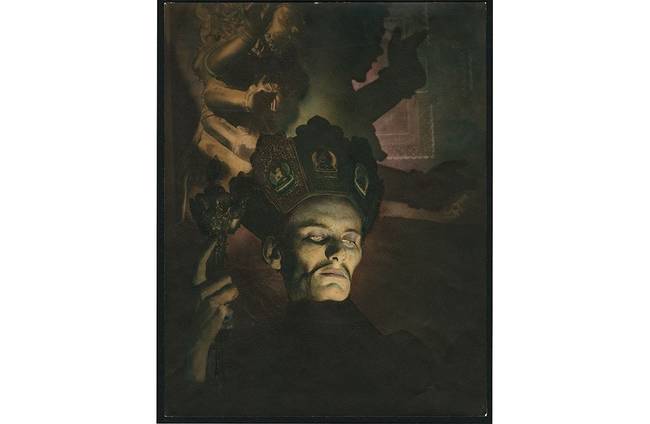

Mortensen focused less on landscape and portraits, and more on fantastical images of Satanic rituals, witchcraft and the occult. His work featured explicit sexuality, monsters, and more. Despite these shocking subjects, his work was regularly featured in the pages of popular magazines from the 30s to the 50s. He was also the author of bestselling instructional books, and ran a photography school where 3,000 aspiring photographers enrolled.

Not everyone was thrilled about this. Ansel Adams, a seminal photographer known for his sharp, realistic images, was not a fan. He was likely put off by the subject matter, or by Mortensen’s habit of retouching his photos so that they looked more like paintings. Either way, Adams considered Mortensen to be an enemy in the photography world. He went so far as to refer to him as “the antichrist.”

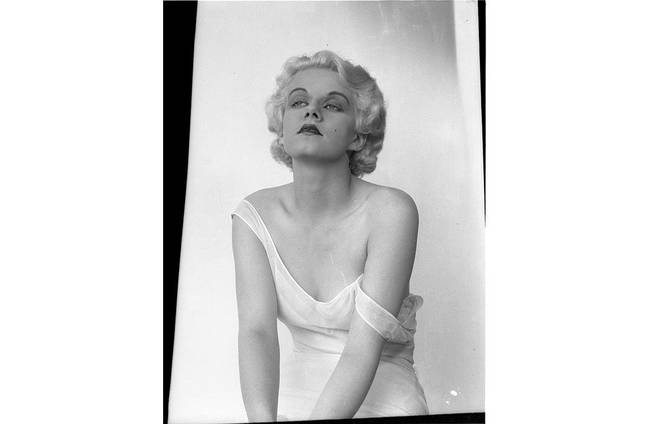

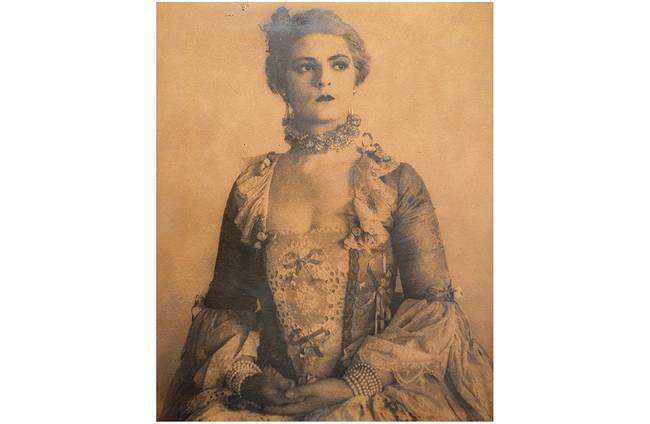

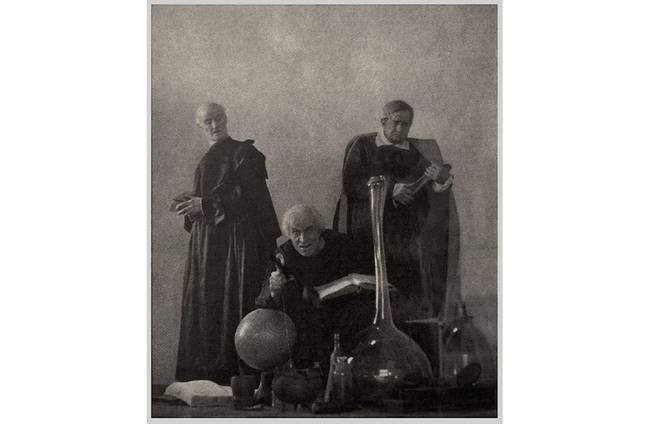

Mortensen studied painting in New York before his foray into the grotesque. He photographed celebrities during the 1920s. He also shot models as historical and mythological figures, and later experimented with surreal, retouched photos blurring the line between painting and photography. Early retouching was done by hand, and a variety of methods were employed to make photos seem more like paintings. Retouching was also used to explore the versatility of the medium. Photos were coated with pigments and emulsions, rubbed with pumice stones and scraped with razors. The intended effect was to create surreal, painting-like images speaking to emotions rather than to the strict documentation that photography was known for.

However, he took interest in composing pieces the way a painter would, and wanted to evoke an emotional response from his audience. He studied up on Jungian psychology, and composed his images based on the patterns that were believed to stimulate the brain’s primal fear responses: diagonals, triangles, and S-shapes. The subjects touched on other basic human feelings, such as sex, sentiment, and awe. Mortensen liked to combine everything into one image, creating a single, deep-reaching burst of uncomfortable emotion.

The grotesque, as these types of images are known, was not a new tradition. It was often found in art (particularly European art) for a long time. Mortensen noticed that photographers tended to shy away from it, and saw it as an area that photography could explore. In Mortensen’s own words, he considered the grotesque to be appealing for “the escape it provides from cramping realism.” He preferred the freedom that the more surreal, imaginative take on photography allowed him. He was also interested in the multimedia approach of early photo retouching, which often looked a lot like painting.

Off for the Sabbot, circa 1927

Madame de Pompadour, circa 1925

Professional Fraternities (The Three Alchemists), 1925

Excerpt from a Pictorial Compendium of Witchcraft, 1926

Tantric Sorcerer, 1932

The public seemed to side with the realists. For one, photography allowed for objective recordings of life, and allowed people (both professional and amateur) to represent their world in a documentary-style way. Additionally, photographs from the real grotesque, such as war atrocities, made Mortensen’s monsters pale in comparison. There was no need for make believe grotesquery in the face of something so horrible.

However, Mortensen is worth looking at again. His blend of the real and the imaginary, of the realistic with the impressionistic or painterly, seems once again relatable. This is all relevant when you consider the advent of digital manipulation, Instagram filters, and other technology that lets us tailor our images to fit the ones we see in our minds.

Via Smithsonian

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share

share